Digest This

Click on the topics below to learn how probiotics can improve your digestive health, naturally.

Exercise Changes Your Gut

- @drHoberman

- Digestive Health, Healthy Aging

Exercise is one of the best things you can do, not only for improving your physical and mental health. Fact is, exercise can help your body work and sleep better and may even help you live longer too.

In some cases, exercise may promote a stronger immune system, based on findings from a pair of related studies on mice and human subjects appearing in Gut Microbes and Medicine & Science in Sports & Science.

Running mice beat colitis

The animal study, conducted by scientists at the University of Illinois and the Mayo Clinic, started by letting a group of mice either run around or be sedentary for most of their lives.

Then, researchers transplanted gut bacteria from those two groups of mice into rodents that were bred to be germ free, so their microbiomes would more easily adapt to the new bugs.

Several weeks later, those younger mice were exposed to chemicals that induced ulcerative colitis to test the health of their microbiomes.

No surprise, those germ-free mice conformed to the bacteria they received, and the changes in their gut health were plain to see. But how?

Mice receiving transplants from active animals experienced less inflammation and healed damaged tissues better and faster than those receiving bacteria from sedentary animals. The tell-tale sign: Higher amounts of gut bugs producing butyrate.

In humans, the presence of butyrate (a short-chain fatty acid) protects your gut from harmful bacteria like E. coli and keeps gut inflammation in check.

The human touch

Researchers took a different approach with their follow-up work on human subjects (18 lean and 14 obese patients). First, patients were assigned to an ongoing cardiovascular exercise program (30-60 minutes, three times per week) for six weeks.

After completing the exercise cycle, microbiome samples were taken, and then a final one after six weeks of no exercise.

Just like their animal counterparts, the guts of humans produced more butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids during the exercise cycle, then declined during the sedentary period of rest.

Also, levels of butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids rose dramatically in the guts of leaner patients, compared to that of obese patients. Moreover, there were very consistent differences in the ratios of gut microbes between obese and leaner patients at every point in the study.

“The bottom line is that there are clear differences in how the microbiome of somebody who is obese versus somebody who is lean responds to exercise,” says Dr. Jeffrey Woods, a University of Illinois professor of kinesiology and community health. “We have more work to do to determine why that is.”

An additional factor that may have been a difference maker on the human side of this study: Patients ate what they wanted and weren’t assigned special diets.

A lot more to learn

There’s more work being done at other research venues to determine how much exercise benefits the human gut and how frequently one needs to be active in order to maintain those healthy rewards.

As is the case with many healthy things, however, the benefits of exercise have their limits, especially when you overwork your body. Pushing it with excessive exercise can become a big problem to the point that it can reverse the physical benefits you hoped to achieve.

Exercising to an extreme can take a huge toll on the health of your gut too, promoting leaky gut in as little as two hours.

However, one of the chemical triggers of leaky gut – the production of zonulin – was eased in a human study by taking a probiotic, like EndoMune Advanced Probiotic, containing multiple strains of beneficial bacteria.

There Is An Endomune Probiotic For Every Lifestyle

-

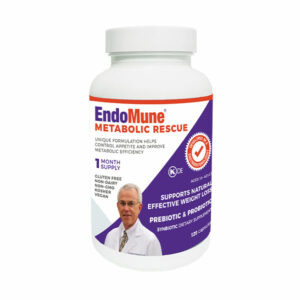

EndoMune Metabolic Rescue

$44.95 -

EndoMune Advanced Probiotic

$42.95 -

EndoMune Companion Pack

$112.93